Featured Member: Brigitte Herremans

Featured Member shines a spotlight on the diverse research interests of, and the exciting projects undertaken by, those affiliated with the Cultural Memory Studies Initiative. In this fifteenth instalment of the series, we speak to Brigitte Herremans, a postdoctoral researcher working on the link between artistic practices and justice efforts in the Syrian and Palestinian contexts. Before joining Ghent University, Dr Herremans was employed in the NGO sector in Brussels for over fifteen years, doing advocacy work on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from a rights-based perspective. In this interview, she talks about her professional journey, the power of the arts in addressing injustices in Syria, and the relationship between memory, human rights, and transitional justice. Addressing the current situation in Syria and Gaza, she states that we do not have the luxury of losing hope in political and human rights activism and solidarity.

Before moving into academia, you worked in the NGO sector in Brussels for several years, focusing on human rights in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Can you talk about those years and what drew you back into academia?

The Middle East has always been central to my academic and professional interests. I did Middle East studies at Ghent University (‘Eastern Languages and Cultures’) and International Relations at the ULB. In both disciplines, my interests revolved strongly around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Almost immediately after returning from Cairo—where I had pursued a postgraduate degree in Arabic—in 2002, I was fortunate that Broederlijk Delen and Pax Christi, two Belgian NGOs, opened a position for a policy officer on the Middle East. In this position, I mainly engaged in advocacy on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from a rights-based perspective, focusing on issues such as settlements, the Wall, the situation in Gaza, and EU-Israel relations. I was also deeply involved in awareness-raising efforts, and I co-authored a book (with Ludo Abicht) titled Israel and Palestine: Maps on the Table, which offers a comprehensive historical overview of the conflict.

Upon the start of the Arab revolutions in 2011, I was very enthusiastic about the attention for the struggle for democracy and human rights. Citizens in the Middle East and North Africa had long protested against repressive regimes, but they had very few channels to do so and attract international attention. It was a moment of upliftment, even though these protests were quickly overshadowed by the restoration of ancient regimes. When the Syrian uprising began, I believed it was crucial to expand our work as NGOs regarding international law and human rights beyond Israel and Palestine to also include the Syrian situation. Firstly, because it is essential to extend our solidarity to other victims and support their struggles. Secondly, because of the scale of the violence.

In 2016, immediately after the publication of my book on Palestine and Israel, I was denied entrance to Israel when accompanying a group. This led me to embark on a new professional endeavour, as a Middle East and North Africa policy officer and coordinator of the Mahmoud Darwish chair at BOZAR, the centre of fine arts in Brussels. At BOZAR, I was able to combine my interest in human rights and literature, showcasing arts from the MENA region. During this period, I also wrote an essay about the potential role of fiction in deepening our understanding of human rights. I was immersing myself in contemporary Syrian literature and was struck by the way in which Syrian writers continued to narrate, witness, resist, and speak truth to power. At the same time, I also noticed the waning interest in Syrian lived experiences and the unfathomable harm they are exposed to. This made me reflect on the capacity of the arts to touch faraway, distant people and render injustices present, or “presence” them.

This eventually encouraged me to embark on a PhD project to scrutinise the potential of literature to shed light on crimes in the Syrian context. Professor Tine Destrooper offered me the opportunity to join the Justice Visions research group. This looks into the participation and mobilisation of victims in transitioning contexts. In the end, what drew me back into academia was the opportunity to contribute to the study of ongoing justice efforts and resistance against injustices. Analysing how literary texts can be potential sites of recognition, resistance, and memory allowed me to somehow offer a response to the growing international passivity. The way I conceive of research is as a practice that is moored in the reality of human rights activists and artists. Academia is the only place where I could investigate the pursuit of justice in the Syrian context while also exploring the emerging role of artistic practices within the struggle for justice.

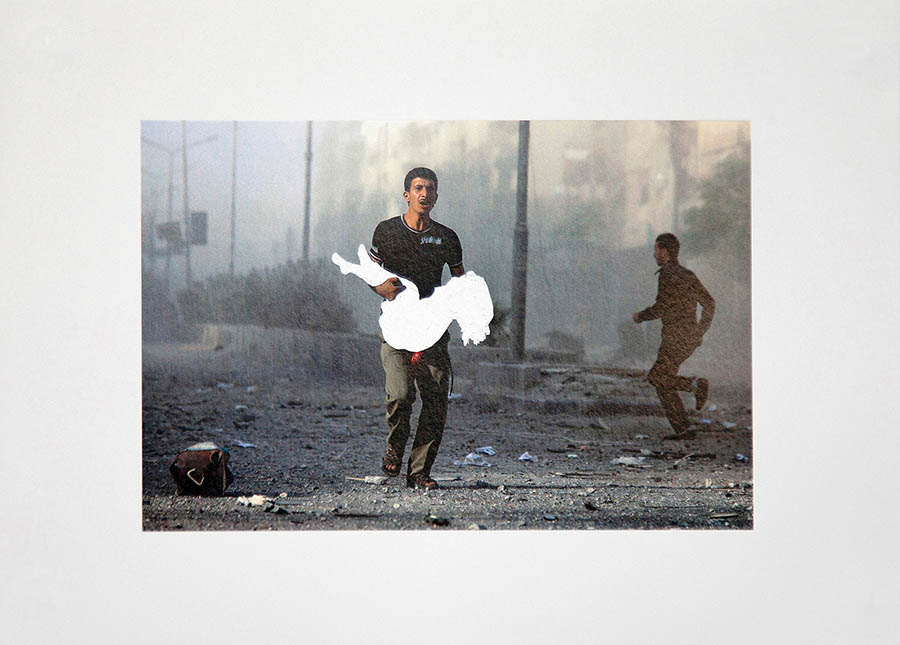

‘Untitled Images’ by Khaled Barakeh

In your PhD you applied the framework of transitional justice to the Syrian context and you considered the role of writers and novels in addressing human rights violations and international crimes in Syria. Can you tell us more about it?

My dissertation, titled “Countering Erasure and Invisibilisation: The Potential of Literature to Open Up the Justice Imagination in the Syrian Context”, centred around the complementarity between contemporary Syrian literary writing and justice efforts. The research question was whether and, if so, how Syrian literary writing can counter the erasure and invisibilisation of injustices. My project investigated how justice efforts and artistic practices, even if they pertain to distinct realms, reinforce and complement one another, particularly in the domain of truth-seeking and memory.

The use of the transitional justice toolkit in the Syrian context might be surprising because of the entrenched non-transition due to the survival of the Assad regime and the transformation of the uprising into a civil war. Yet, it proved to be the sole paradigm that justice actors could apply in the context of the fast-growing accountability gap and the dwindling international interest in Syria. Justice actors used the transitional justice paradigm in their pursuit of justice, furthering their resistance against authoritarianism and international crimes, spearheading initiatives in the field of documentation, criminal accountability, and truth-seeking. Moreover, because of the lack of formal justice avenues such as criminal proceedings, informal initiatives became essential sites of innovation and disruption. In my research, I looked into the way in which literature can complement ongoing justice efforts. Many Syrian writers share the aspiration of justice actors to bear witness and counter what they see as forcible forgetting. Drawing from empirical research conducted with Syrian writers, I demonstrated that literary writing can “presence” experiences of harm, foreground multiple truth claims, and allow for epistemic resistance. Empirical reader response research led me to conclude that literary writings can serve as – fictional – recordings of harm and echo experiences that were invisibilised or erased.

You now carry out research in the Faculty of Law, exploring the role of the arts in addressing human rights violations. Can you talk about your current research and how it intersects with memory studies?

In my postdoctoral research, within the iBOF project “Futureproofing human rights: Developing thicker forms of accountability”, I continue to focus on the nexus between artistic practices and justice efforts in the Syrian context, and I look more specifically into the issue of avenues for accountability besides the judicial realm. I am also extending this line of research to the Palestinian context. With regard to Syria, my key interest is to look into the way in which informal practices in the domain of truth-seeking (e.g. initiatives by family members of the forcibly disappeared to look for the fate and whereabouts of the missing) can expand the sites of truth-seeking and memorialisation. In the Palestinian context, I will investigate how narrative accounts of harm can complement our understanding about the large-scale international crimes that take place in Gaza. According to Lyndsey Stonebridge, literary writings create imaginative terms by which it is possible to see and truly comprehend injustice, as they disclose hidden connections and injustices.

An important feature of Syrian literary writing is dissent. Through fiction, writers have historically pushed back against the Assad regime’s imposed silences about crimes (e.g. through prison writing or novels about the Hama massacres that happened in 1982). The late Syrian literary scholar Hassan Abbas wrote about “stories against forgetting”. As such, we can think of Syrian narratives as offering a way to counter forcible forgetting and to memorialise overlooked lives. This is where the link with memory studies is articulated most strongly. My research examines the role of literature in providing ways to “presence” experiences of harm that have been glossed over, thus contributing to shaping the memory of these experiences. I conceive of it as informal archives.

Sit-In for the Missing and the Disappeared, the Syria Campaign

Your expertise is highly interdisciplinary and has much in common with the study of cultural memory. How do you see the relationship between the different fields of scholarship you work across, which include human rights, transnational justice, literature, cinema, and memory studies?

Both in my theoretical and in my methodological approach, I attempt to incorporate multiple perspectives, drawing on transitional justice scholarship and literary studies. This was particularly the case in the focus groups I ran with readers, in which I mixed methods from the social sciences and literary studies. This research would not have been possible without effectively engaging in what can be seen as an elaborate bricolage.

Central in my approach is the potential of the arts to create awareness about human rights violations and enrich our understanding of the impact of injustices. Without instrumentalising artistic practices, I approach literary writing and cinema as important avenues to communicate experiences of harm. I do indeed draw from different fields of scholarship, recognising that boundaries between disciplines and perspectives are not always that strict. In the domain of literary studies, there is a growing body of scholarship on the intersection between literature and human rights. Similarly, within transitional justice scholarship, particularly in the critical transitional justice school that is rooted in practice and focused on the transformative potential of transitional justice, there is a keen interest in the role of the arts.

Which works of memory studies have been particularly important in your development as a scholar?

The scholarship of Ann Rigney and Mihaela Mihai strongly inspired my perspectives on the potential of artistic practices to contribute to the pursuit of justice. In particular, I rely on Rigney’s work, showing how the arts can be seen as catalysts in creating new memories, supplementing what has been documented with different understandings. Rigney fed my thinking regarding how literature can challenge our thinking about what is worth remembering, and how narratives can play a role in remaking memory. Her concept of mnemonic change was of paramount importance for my reader response research. Particularly interesting is how she suggests two different strategies to create mnemonic change or to “enable” forgotten histories: either integrating memories into existing narrative schemata or using the literary technique of “defamiliarisation”, coined by Viktor Shlovsky. Secondly, I was strongly influenced by the work of Stef Craps and Michael Rothberg, who critically analyse the persistent dominance of Eurocentric perspectives that centre the memory of the Shoah. Their work made me understand better how the perception that the atrocities of Europe are “morally more significant than atrocities elsewhere” entails an unequal distribution of empathy for different victim groups. Unsurprisingly, Rothberg’s concept of “multidirectionality” as a strategy to enhance the memorability of hidden histories and include disconnected groups in narratives has also been key for my thinking. Of particular importance was Rothberg’s exploration of the role of immigrants in critical memory work. In their literary texts that address experiences of harm, they can simultaneously offer a relational and multidirectional memory that does not deny the specificity of the Shoah. I put this critical memory work of Syrian activists and artists in relation to my research on the way the Syrian arts can counter erasure and invisibilisation

What can memory studies scholars learn from research done in the domain of human rights and transitional justice? Can you recommend some works from the latter fields that are particularly relevant for people working on memory?

There are so many lessons to be learned, but what I find particularly worth exploring is the shared interest in the field of memory studies and contemporary transitional justice scholarship in epistemic violence. In both fields there is a growing interest in informal practices and the way in which grassroots activism is essential to reshape memories of overlooked experiences or marginalised lives. Within the transitional justice paradigm, it is noteworthy that memorialisation has been identified lately as a separate fifth pillar, alongside criminal proceedings, truth-seeking, institutional reforms, and repair. I hope that this will generate interest in the weaponisation of memory in conflicts. As for concrete scholarly works, I think that the work of Miranda Fricker and José Medina on epistemic injustice and resistance (see The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice) holds particular value for memory scholars. Habib Nassar and Noha Aboueldahab have done groundbreaking research about resistance in transitional justice initiatives, shedding light on the importance of local (transitional) justice actors’ agency in adapting transitional justice initiatives to the local context, making them relevant to advance revolutionary objectives and resist experiences of past and ongoing injustices. Thus, they turn highly standardised and depoliticized approaches to justice into “a combative, activist and creative discipline”, in the words of Habib Nassar.

Sit-In for the Missing and the Disappeared, the Syria Campaign

You have dedicated many years of your life to the Palestinian cause, which has grabbed the world’s attention for the past several months as a result of the crimes committed by Hamas on 7 October and the dreadful response of the Israeli government. In your opinion, does memory play a role in the current conflict?

Memory plays a hugely important role when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian question, firstly because of the erasure and invisibilisation of Palestinian experiences of harm, and secondly because of the weaponisation of memory. Besides Israel’s violence, Palestinians have been exposed to the suppression of their narratives in policy circles and media in the Global North. Memories about experiences such as the Nakba (the mass displacement of Palestinians in 1947-1949) have been suppressed by Israel. Besides scholarly research, media work, and NGO reports, fictional accounts (e.g. the film Farha, or the novel Gate of the Sun by Elias Koury) have played an important role in keeping the memory of these experiences alive. Another important issue is the weaponisation of the memory of the Shoah by Israeli and (mostly) German politicians. While this phenomenon is not new, with instances dating back to the Lebanon War in 1982, it has become increasingly pronounced lately, particularly during the ongoing Gaza war. What is interesting is that an increasing number of scholars of the Shoah and in the field of genocide studies are taking a stand against the manipulation of the memory of the Shoah to distort historical facts, particularly in the context of Israeli mass violence against Palestinians.

As an activist and expert on the Middle East and human rights, would you mind ending this interview with a comment on the current situation? Should we have hope for the future of human rights? Do you think that memory studies scholars can have any positive impact whatsoever?

This is a pitch-black period for human rights, as the population of Gaza is facing annihilation policies, with Israel clearly being intent on destroying the possibility of future civilian life. With regard to Syria, there is also no prospect of positive change, with the Assad regime continuing its repressive policies, in particular the enforced disappearance and massive imprisonment of citizens. Yet, we do not have the luxury of abandoning hope. As Rebecca Solnit states in Hope in the Dark : “to hope is to give yourself to the future—and that commitment to the future is what makes the present inhabitable.” What makes the present in Palestine, Syria, and so many other places where civilians face mass violence inhabitable, is the ongoing resistance of local dissidents, who are continuing their struggles for justice, and who need the solidarity and help of activists and scholars in the Global North. Concretely in the case of Palestine, we see that memory scholars are pushing back against the weaponisation of the Shoah and the politicisation of the definition of antisemitism (by the IHRA), and this has been of huge importance.

Interview conducted via email by Guido Bartolini and Stef Craps.